Whenever I’m in Scotland at this time of year I cannot help but think of Halloween and the build up of excitement ahead of the yearly Scottish tradition (for children) of ‘guising’ – the original Celtic version of the American trick-or-treating. As a child the whole month of October would be spend creating an outfit – usually something spooky, but not always – and learning a song or a poem to recite on our neighbours’ doorsteps in return for fruits, nuts or sweets, as well as gouging out turnip lanterns to carry. Nowadays everyone in the United Kingdom knows about the custom through the spread of the American tradition, but in the 1970s guising wasn’t practised much outside of Scotland and Ireland. This was something I only discovered when we had to patiently explain what we were up to in our strange costumes to a new English neighbour, who then confessed he had nothing to give us but coins from his pocket. We accepted the silver five-pence pieces, but rather guiltily, as our parents had told us never to take money from the households we visited.

Thinking back to that autumn night when we confused our English neighbour, I can remember nothing of what my best friend and our little sisters were wearing, only that my mother had helped me to customise an old red velvet evening dress she’d worn as a teenager in the 1950s (itself created from a young aunt’s evening dress) and declared myself to be a pillar box. This was more about the fact that velvet was my favourite material and red my favourite colour than any resemblance to an actual post box. Of course my disguise had to be explained at every door we visited and once that was done I launched into a tuneless version of Ye Banks and Braes o’ Bonnie Doon, which I thought would mark me out as a budding folk singer. A year later I was told by a vindictive teacher that I was tone deaf and never sang in public again. And many years after that, when as a student I started raiding my mother’s collection of (now) retro outfits, I regretted cutting up that dress so much!

Unfortunately no-one thought to take any photographs of us in our outfits and neither it seemed did any of my other Scottish relatives have their Halloween costumes captured for posterity. This was possibly because of the fact that it would have been difficult to take pictures at night, even supposing a family did own a camera. But my mother told me that when she and her young friend Jim were dressed up in their guising outfits, her father would smear their faces with soot that he collected by putting his hand up the chimney. I have since discovered that this was an old custom of early guisers from the 1600s, as ash was deemed to keep away evil spirits. But by the time I was into guising in the early 1970s, that tradition had faded out and cardboard masks were used to hide our faces. Even now, the smell of rough cardboard brings back that nervous feeling of pulling on our gaudy masks as we were about to knock (or ‘chap’) on yet another door.

Please to help the guisers, we’ll sing you a merry wee song! That was what my mother and Jim said as they stood in their neighbour’s doorways in Edinburgh in the 1940s with their soot-smeared faces and ghost-sheets, their emergence into guising age (around seven) coinciding with the end of the war. Like most children, their excitement was not about the gains, although having some goodies to take to school the next day to compare with the ‘hauls’ of classmates would have been an added bonus. The anticipation surrounding the event was more about creating the ideal costume from what was to be found lying around at home, then being out at night unaccompanied by adults, and for some children (like myself and my mother) the chance to show off. Of course the whole scary nature of the event was the icing on the cake and the fact that the last day in October coincided with the clocks moving back, plunging the outside into darkness before we had even finished our dinner, made it feel even more of an adventure. We knew on some primeval level – even if it was never explained to us – that what we were ‘celebrating’ was the return of the dark.

As we grew older, guising was replaced by Halloween parties and discos run by the school or the church. Like many teenagers of the fifties, my mother was very involved with her local church youth club, which she attended from age 14 to 20. This group was held on a Saturday night and involved dances, talks, amateur dramatics, games, trips away and retreats and summer hay rides. In the days when the church was the focus of the community this was an ideal way to meet other young people and future partners. Parties were held at key dates, such as Xmas, Valentine’s Day and of course at Halloween where games like ‘dooking’ (ducking) for apples were played.

Corstorphine Old Parish Church, Youth Club Halloween Party, 1958

Corstorphine Old Parish Church, Youth Club Halloween Party, 1958

Although there are no other Halloween images in my family’s collection, there are images of people in various costumes for other reasons. One of my favourites is that of my grandfather’s younger brother, John McKay, dressed up while collecting for charity during Glasgow University rag week in the 1930s. A student in a working class family in those days was a rare thing indeed, and in such a religious family one who was studying theology was even more of a cachet. Yet just after he trained as a minister of the Church of Scotland, John caught tuberculosis and died at the age of twenty-four, unable to devote his life to the service of the Church as he’d wished. A popular and devoted preacher, as well as a loyal friend and brother, he left a gap in many people’s lives.

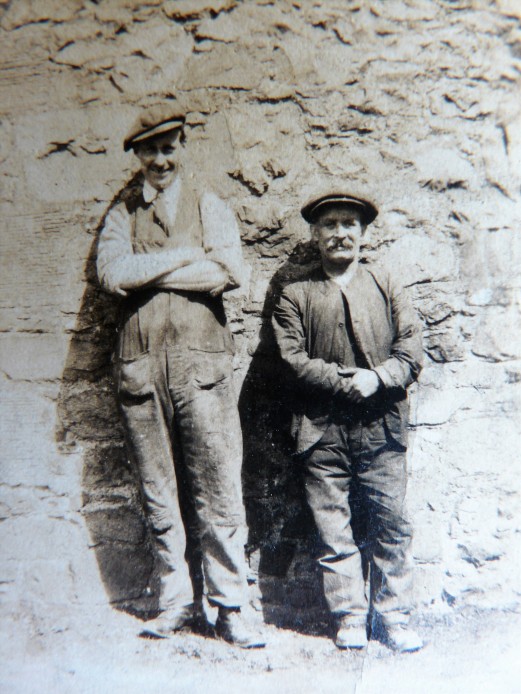

John McKay and friend at Glasgow University rag week, late 1920s

John McKay and friend at Glasgow University rag week, late 1920s

Dressing up appeared to be in vogue in the 1920s as many of my grandparent’s snapshots from holidays with their friends can attest to. A small booklet of snaps from a local photographer’s in Rothesay in West Scotland, shows a group of young people, including my grandmother and one of her sisters all having fun at some sort of resort. This was possibly around about the same time she started dating my grandfather – although he is not there in the pictures. It was perhaps a family holiday where the young folk mingled with each other, but the parents were still there to keep an eye on everything, or older siblings and cousins took over that role.

Dressing up at Rothesay, c1925

Dressing up at Rothesay, c1925

Looking closely at the photograph it would appear as if everyone has raided the dressing up box at their accommodation, mixing styles in an ad hoc way. I almost did not recognise my grandmother, who is standing with the young man and holding the parasol. Her companion appears to be trying to emulate Rudolph Valentino in The Sheik – a silent film that had come out in 1921 and had given Valentino his big break. The follow up The Son of the Sheik came out five years later and was the last film Valentino made before his death in 1926, which may mean that the photograph above was taken in that year. As the film was also a box office hit, it would have been seen by most young people, particularly the women who adored Valentino, dubbed the ‘Latin Lover’ by the studios and the first screen sex symbol of the 20th century.

Poster for ‘The Son of the Sheik’ (c) United Artists

Poster for ‘The Son of the Sheik’ (c) United Artists

An important celebration in Scotland was New Year – that other pagan Celtic holiday. Christmas was not a public holiday in Scotland until 1958 and New Year was when all the revelry took place instead. This image (below) shows my great-grandmother, by then a widow, playing a game (which involved eating chocolate in fancy dress) that I remember from my own childhood. Her oldest son Adam is standing over her next to various sisters-in-law. This annual party was held at Adam and Lilly’s house on New Year’s Day and my mother remembers it as a chance to drink lemonade and eat pickles and be spoilt and petted by all the grown ups present.

My great-grandmother at New Year, 1950s

My great-grandmother at New Year, 1950s

As a child, I always felt that Halloween marked the beginning of the wintery count down to Christmas, with Guy Fawkes Night to help us on the way to the main event shortly afterwards (a custom my father had been much more involved in as a child in London, with his ‘penny for the guy’-ing). By the 1970s Scotland had finally fully embraced Christmas, and having a London-born father also meant that much more weight was given to the English traditions of the festive period. Thus I was able to fully partake in the annual traditions from both sides of the border, gaining support and encouragement from the parent whose customs were being celebrated at the time.

Wishing everyone a very happy Halloween!

The Incidental Genealogist, October 2023

P.S. Due to current writing and study commitments, I will be posting every quarter instead of monthly from now on.

Girl in a Graveyard

Girl in a Graveyard An Immortelle (c) Market Lavington Museum – link to website here

An Immortelle (c) Market Lavington Museum – link to website here

Yours Sincerely, Lilly, Jan 1920

Yours Sincerely, Lilly, Jan 1920 Adam Neilson and Lilly Blythe, early 1920s

Adam Neilson and Lilly Blythe, early 1920s